Developing value chains to use invasive alien species has always been a contentious idea. Some argue that it provides more resources to deal with invasions and upscale eradication efforts, in a context where such resources are dramatically lacking. Others consider that it might make things worse by reducing incentives to eradicate invasive species once the demand for their biomass is established; this is on top of the fact that private actors are only interested in low cost production rather than investing in long term restoration – things might take a wrong turn.

It might thus look even more controversial to assume that carbon markets could help such value chains to thrive. Indeed, why cutting down trees should be rewarded with carbon credits as it looks like it leads to more emissions and less climate change mitigation? How surprising that it might sound, there is actually a case for it as this new paper shows.

Indeed, the first question adressed by the authors is whether such value chains would be eligible as carbon projects and carbon credits’ issuance by the main certification standards. This is not straightforward and it depends not only on the specific projects but also on the standards and their principles. To make things simple, either the woody biomass is harvested explicitly for the value chain itself (tree logging would not take place without the value chain), or this woody biomass lies on the ground after logging for land rehabilitation purposes and is availabe for collection. In the latter case, the value chain is only responsible for the processing of the biomass that can be used as a substitute to fossil fuels with reduced emissions in the process.

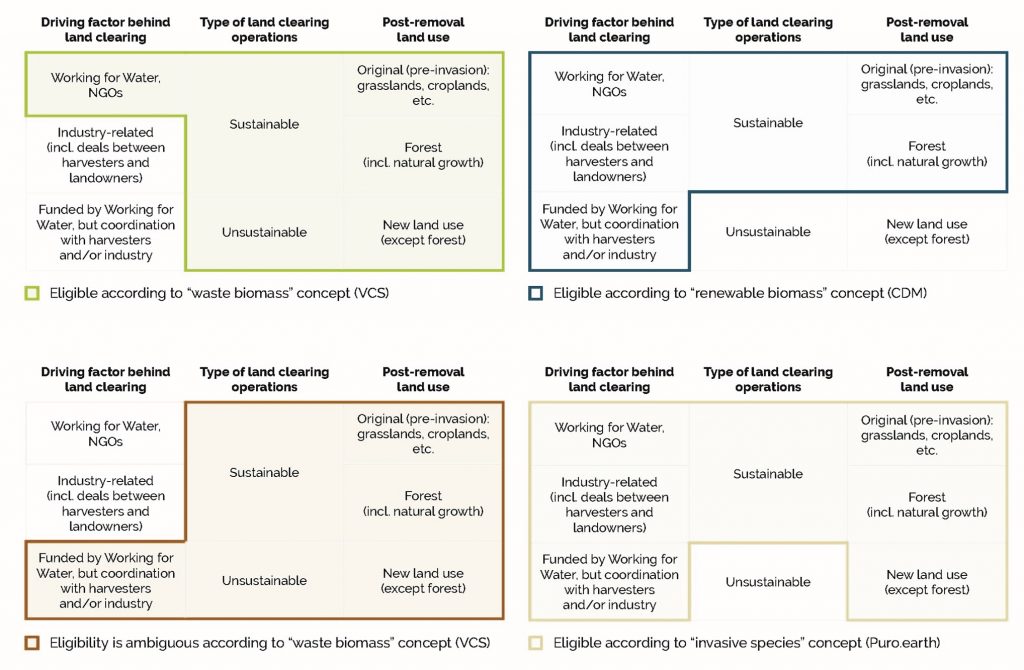

But the certification standards do not all operate similarly and eligibility is assessed variously with different criteria and principles. Basically, two approaches co-exist: “renewable biomass” that refers to the sustainability of the harvesting operations and the return to the natural land use after biomass collection (e.g. forest restoration), and “waste biomass” that focuses on the fact that trees were already cut down and the biomass was about to be burned or left to decay (Figure 1). With renewable biomass the rationale is that carbon stocks will be reconstituted with plant regrowth, while for waste biomass the rationale is that its use will substitute emissions from other sources (e.g. bioenergy instead of fossil fuels). The weak part is that the application of one or the other approach to a same situation can lead to a different assessment of eligibility, which questions their robustness to guarantee mitigation impacts for a given project.

Figure 1: Situations leading to eligibility of using invasive trees biomass for the issuance of carbon credits according to standards’ methodologies.

Figure 1: Situations leading to eligibility of using invasive trees biomass for the issuance of carbon credits according to standards’ methodologies.

The other question addressed by the authors is whether the revenues from carbon credits would make a difference to the financial feasibility of the value chains. Indeed, the objective is that carbon credits would make investors change their decisions to move forward with the use of biomass from invasive alien trees due to higher expected revenues overall, otherwise they are useless and unjustified from a climate change mitigation perspective. Indeed, it would equate to issue carbon credits for a business-as-usual project that does not lead to reduced emissions. To do so the authors assessed methodologies corresponding to three value chains – biochar and heat production on small and industrial scales respectively – with the quantification of reduced emissions based on life cycle analysis.

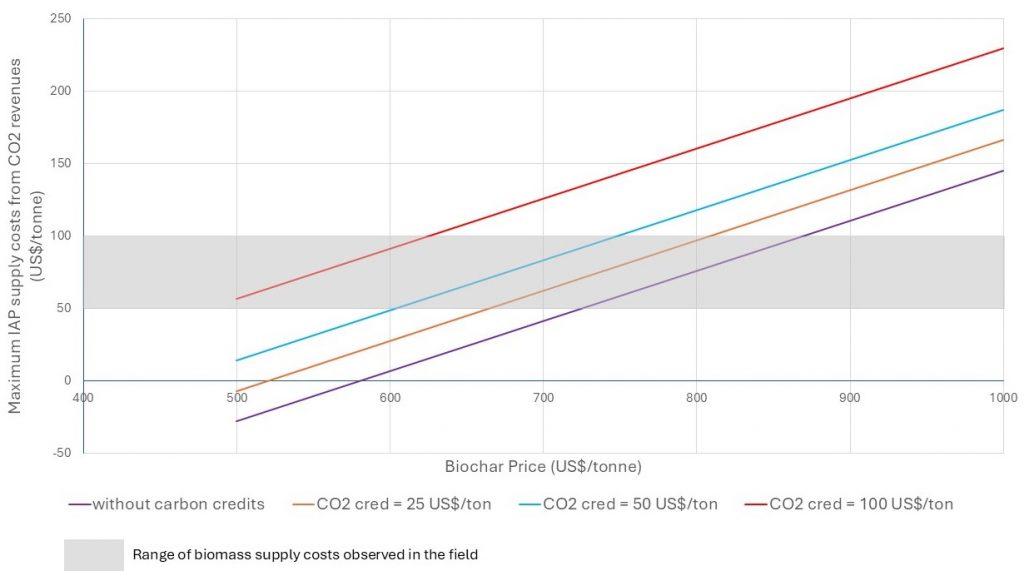

Worth noting, results were contrasted depending on the value chains but overall carbon incentives can make a difference with up to 20% of the final product value. To make things clearer and more explicit, the authors translated the carbon incentives into an increase of the maximum price that could be paid for the biomass while keeping the business profitable (case for biochar in Figure 2). It showed an increase of 8–95% depending on value chains. When comparing these numbers with the average price charged in South Africa for such biomass supplies, the authors further concluded that carbon credits could provide the means to collect biomass from invasive alien trees in areas otherwise inaccessible.

Figure 2: Relationship between market price of carbon credits, maximum biomass supply costs and biochar market price.

This study shows that carbon markets could contribute to the management and eradication of invasive alien trees despite disputable mitigation impacts, but that value chains must also rely on solid markets for their end products. While such results dot not mean that carbon projects are going to multiply in this space – for instance transaction costs involved could substantially reduce the incentives and uncertainties could put off project developers -, they are nevertheless encouraging. Yet such projects would remain subject to scrutiny and criticism for at least two reasons: the long term impacts on invasions, and the actual mitigation impacts. At the time when tree invasions in Southern Africa are a huge issue and the world is desperate for mitigation impacts, this avenue should thus be both explored further and kept under intense scrutiny! For instance, calculations should be refined with the inclusion of more projects but also the consideration of cost differences between sites to guide investors towards the most promising opportunities.

Read the paper

Pirard, R.; Petersen, A.M.; Grobler, A. ; Tuchten, O.F. 2025. Carbon markets can support invasive trees’ control with biomass-based value chains. International Forestry Review, Volume 27, Number 1, March 2025, pp. 94-110(17). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1505/146554825839764896

For more information, contact Romain Pirard at pirardr@sun.ac.za